“Providing activities that relate to students and capture their interests is a best practice. However, if we want such activities to produce genuine student growth, instructional design must focus on learning outcomes as opposed to the activity itself.”

To this day, one of my favorite all time songs is Fly Me to the Moon, preferably versions sung by Frank Sinatra. There exists a remote possibility of a connection between this preference and my 7th grade science fair project. When I was in 7th grade, the Apollo

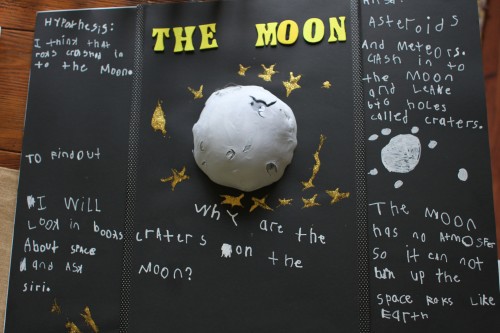

Over the next several weeks, my dad dutifully drove me over to Scott’s house, where we diligently toiled away for hours on our moon project. Not surprisingly, our project involved paper mache, glue, sawdust, spray paint, and plastic plants, buildings, and human figurines. It also included plastic domes and plastic tubing which connected the “Residential” dome to the “Community” dome to the “Workplace” dome. When finally finished, Scott and I beamed with pride and the smug knowledge that our science fair project would be feted as a masterpiece and we would walk away as first place winners at the annual science fair competition. As we marveled at our finished product, my friend reminded me that we were also supposed to do some research and write a paper determining whether man could actually live on the moon. We threw a few sentences down on paper and prepared for the big event, arguing about who would keep the first place ribbon at their house first.

|

| via: goo.gl/IXD2Xz |

|

| via: goo.gl/Mi6EtA |

Although we honestly had no clue at the time why our jaw-dropping project merited zero recognition from the judges, I suspect anyone reading this today has already diagnosed the problem. Our “Science” project was a tad short on “science” even though it was a stunning art project. In fact, we learned nothing at all related to our proposed question about whether living on the moon was feasible. Although I can still recall with great clarity the work we put into the model of the moon, I recall no reading or research we did about the actual question itself. I suspect our “scientific” paper merely described our art project and included nary a word about any scientific considerations pertaining to living on the moon.

Although science fair projects have come a long way in terms of rigor and academic focus since my junior high days, I still worry at times if, in an ever-present quest to “innovate” in our classrooms, we are sacrificing “learning” in the process. Although I am a firm believer in engaging students through high-interest activities and projects and using flashy technology tools to enhance such work, I am perhaps even more adamant that these activities, projects, and technologies must relate to specific learning outcomes designed to grow our students’ knowledge and skills. Over the course of my career in education, I have seen the education pendulum swing from one extreme to another and back yet again, with the two extremes being some version of “traditional” learning and some version of “innovative” learning. Today we are in the most innovative educational environment I have witnessed in decades. My fear, however, is that if we do not remain steadfastly focused on learning outcomes and results, we may soon see the pendulum sway back once more, with a concomitant outcry of of folks demanding a “back to basics” approach to public education. As with almost all educational concerns, we cannot be forced into one or the other. We must continue to provide “innovative” learning experiences, complete with authentic projects and exciting learning activities, but we cannot lose sight of the “learning,” the knowledge and skills students must acquire in the process.

|

| via: goo.gl/E55nx4 |